When thinking about evolution, one must also consider natural selection and the role it plays in evolution. We have alleles to thank for natural selection. Alleles are the genes that determine everything from fur color to height to speed. If there is an allele that determines one trait is better suited than another to the environment an organism is in, then it tends to stick around and go to their offspring. Eventually, this trait dominates and becomes widespread throughout the population.

The dominant allele is the trait we see, and the recessive allele is the one that gets pushed to the back. If we look at the peppered moth, ‘D’ is the dominant trait and ‘d’ is the recessive trait. An organism that had ‘DD’ or ‘Dd’ would be dark, but an organism that had ‘dd’ would be light.

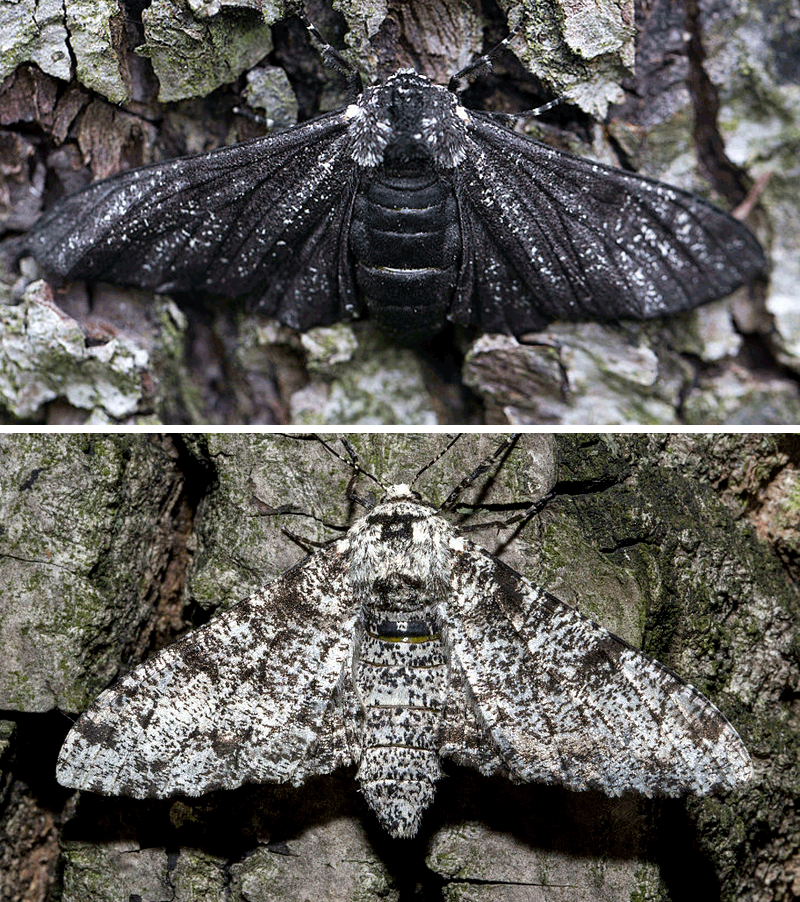

During this experiment, we were looking at how the peppered moth would change from generation to generation across varying amounts of pollution. We used little paper moths and a black poster board with white squares to show pollution. Below, you can see the two different morphs, or types, of moths we were inspecting. The dark morph, ‘DD’ or ‘Dd’, typically survives better in a more industrially polluted area, as the soot stains the trees and makes the bark darker. The lighter moth, ‘dd’, does better in less polluted areas where the bark is cleaner.

Images by Jerzystrzelecki.

In the low pollution scenario, the lighter moth did better than the darker. With the trees that the moths rested being whiter and less polluted, the dark moth stood out and was more easily seen by predators. Thus, the dark gene was actually lost completely. We ended up with only the light moths surviving, and all the dark ones being eaten. While this is good for the light moths, it severely decreased the genetic variation within this population. This decrease could eventually lead to their extinction because all populations need to have some variance so it can bounce back from any disasters.

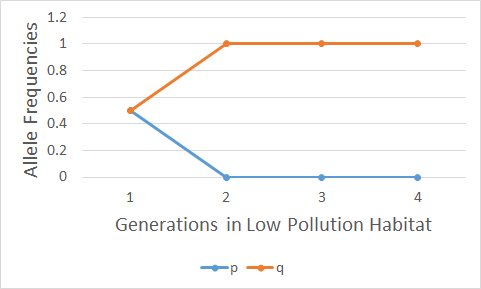

The graphs below shows the different frequencies for the dominant and recessive alleles in a low pollution habitat. In Graph 1, ‘p’ represents the dominant dark allele ‘D’, and ‘q’ represents the recessive light allele ‘d.’ We can see how the light moth takes over the environment and survives. The dark moth, however, didn’t even make it to the next generation. In Graph 2, we can see that neither the ‘Dd’ nor the ‘DD’ genotypes make it through the first generation. The dark moth is simply too easy to spot, so it unfortunately becomes the first one to be eaten.

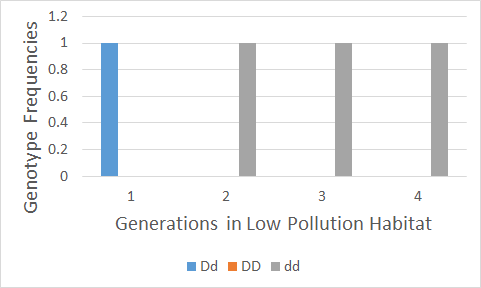

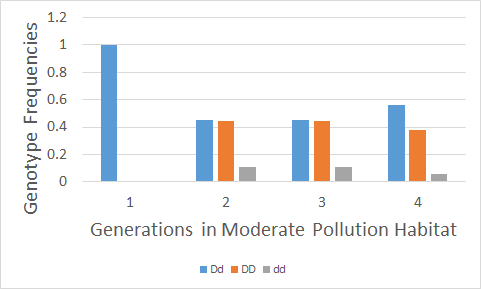

In the moderate pollution scenario, the darker moth fared much better. It survived and thrived on the soot covered tree bark. There was a pretty good mixture of the moths, which made for good variation. However, the light morph is steadily declining. Because of the increased variation, though, it could come back in later generations. If a ‘Dd’ mates with another ‘Dd’, they have the potential to make a ‘dd’ offspring, which in turn would lead to the return of the light moths.

These graphs show the frequencies of alleles in a moderately polluted area. Graph 3 shows the opposite of Graph 1. The dominant allele is better equipped to handle the dark bark than the recessive allele, and the graphs reflect that. While neither morph disappears like we saw in the low pollution scenario, it is clear that the light moth is at a major disadvantage.

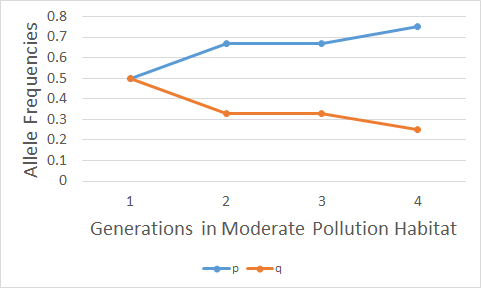

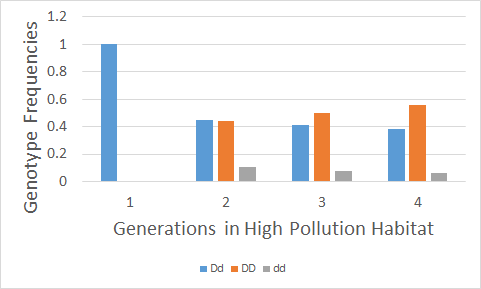

The last scenario we ran was the high pollution environment. After running the other two tests, we held out little hope that the light moth would survive for very long. The expectation was that we would see a repeat of the low pollution area, but with the disappearance of the light moths instead of the dark moths. However, the light moths stayed around for every generation. This was probably due to the fact that two ‘Dd’ could mate and produce a light offspring.

The two graphs below show the frequencies of alleles in the highly polluted environment. While it is very similar to the moderate pollution, we can see that there are fewer recessive alleles in this area.

In the wild, we are seeing a decrease in the dark morph. While they were thriving when there was heavy pollution in the area, but the Industrial Revolution has come to an end and the trees are starting to become clean again. This is now leading to the light moths being camouflaged, and the dark moths becoming the main prey again. “The rise in frequency of the dark form of the moth and a decrease in the pale form was the result of differential predation by birds, the melanic form being more cyptic than [the pale form] in industrial areas where the tree bark was darkened by air pollution,” (Majerus et. al, 2000). We can plainly see how genes and predation can lead to natural selection, even though the process may be reversing itself now.

Evolution can be thought of in another way as well: artificial selection. This refers to the way humans can select for the genes they deem desirable. Breeders take the organisms with the favorable genes and reproduction takes it course. This typically leads to expressions we would not normally see in nature. If we take the fox domestication experiment performed by Belyaey, for example, we can see how artificial selection can change a species entirely.

When Belyaey was thinking of genetics, he came across the thought of the different dog breeds we have. How could we get so many different from just the wolf? He decided to look at the fox and wanted to try domesticating them, too. Domestication needs two things to be successful: tameness and low aggression. So when Belyaey was mating the foxes, he would only pair the ones with low fear and low aggression together. “Only those foxes that were least fearful and least aggressive were chosen for breeding,” (Goldman, 2010). To prove the study was accurate, he did the same thing with the aggressive and fearful foxes.

Out of this study, Belyaey expected to see more tameness and less aggression from the foxes. However, he did not expect the domesticated foxes to change fur colors, have droopy ears, or have short or curly tails. With the aggressive foxes, he saw no change whatsoever.

This experiment goes to show that when we start messing with nature and artificially select genes for our own benefit, we could be seriously harming the population. We are altering the evolutionary process in ways we cannot even imagine. This artificial selection is causing less genetic variation, and we are even losing some species. When selecting for favorable or desirable genes, humans are actually changing the natural order of the environment and potentially damaging the species as a whole.

Goldman, J.G. (2010, September 6). Man’s new best friend? A forgotten Russian experiment in fox domestication [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/blackboard.learn.xythos.prod/59442bc14e926/10408?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%2A%3DUTF-8%27%27Man%2527s%2520new%2520best%2520friend%2520%2520A%2520forgotten%2520Russian%2520experiment%2520in%2520fox%2520domestication%2520.pdf&response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Date=20190304T185133Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=21600&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAIL7WQYDOOHAZJGWQ%2F20190304%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Signature=45e973b14bbbbbb7bc2626e302c8f649cea9dc84ed51789eefe3ba7f1aaf68e5

Majerus, M. E. N., Brunton, C. F. A., & Stalker, J. (2000). A bird’s eye view of the peppered moth. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 13(2), 155-159. http://www.esalq.usp.br/lepse/imgs/conteudo_thumb/A-birds-eye-view-of-the-peppered-moth.pdf