Thermoregulation is how an animal keeps its inside body heat at a suitable temperature. It is a process that allows some animals to survive in the harshest environments, and others to thrive in the more moderate areas.

There are different types of temperature regulating in animals: ectothermic and endothermic. An ectotherm, or cold-blooded animal, typically relies on the outside environment as a source of body heat and their internal temperature changes with the environment. This group includes reptiles, fish, and some insects. Endotherms, or warm-blooded animals, however, produce their own body heat and keep a constant internal temperature. These would be our birds and mammals.

We decided to do an experiment on body size and how it can affect an organism’s thermoregultion. Because “body size affects an herbivore’s thermal balance through metabolism [and] body surface area,” (Belovsky, et al., 1986) we hypothesized that if temperature loss is dependent on an organism’s size, then a smaller organism will heat up and cool off faster than a larger one.

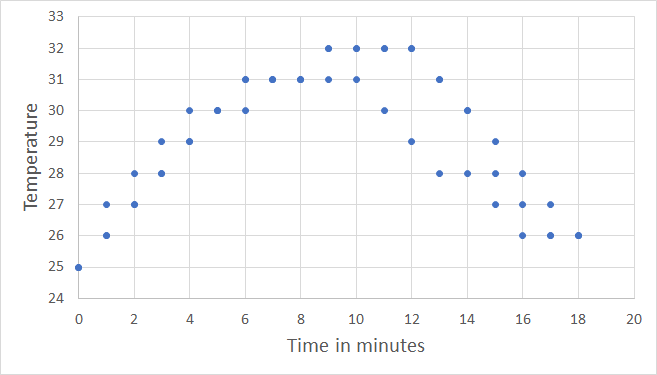

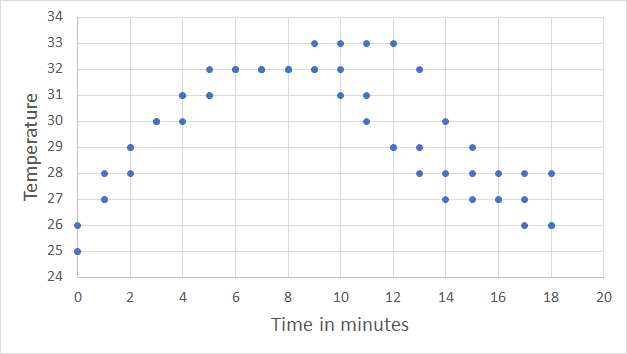

Two aluminum foil bunnies, one large and one small, were filled with cotton balls. The cotton balls mimic how a warm-blooded animal can sustain its own body heat by soaking in the warm rays from a heat lamp and trapping it. Since the experiment is testing size difference, one bunny has 6 cotton balls inside, and the other has 12 cotton balls inside. This “doubling in size” would provide a decent size ratio to go off of for the tests.

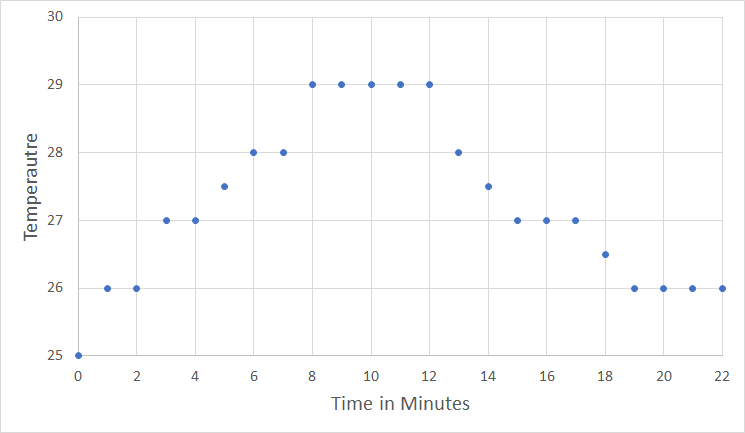

Before any actual testing could be done, we first had to find the heating curve by which our bunnies would be tested against. This curve, in Chart 1, shows how an empty aluminum foil cube heats and cools. It serves as background information on how quickly a regular object reacts to the heating lamp, and gives a basis for us to make our predictions.

There were three rounds of heating and cooling for each bunny, with all three rounds lasting a total of 18 minutes. Because only body size and temperature were being compared, a student t-test was calculated to find if the two were correlated. The results of this test, called the p-value, shows what the data is telling us and is based on whether the value we get is greater than or less than 0.05. We found that the p-value was 0.17, which is greater than 0.05, so there is more of a difference in the two bunnies than we originally thought.

In conclusion, we decided that the size difference must be truly enormous for the internal body temperature to be severely affected. If this test had been between a whale and a bunny, we may have seen a more drastic change between the two animals. However, this does show that while size might matter between the larger animals, being a bunny of any size does not have any negative side effects and only proves they are the superior mammal.

While we can look at simple, two-dimensional factors all day long, we must also take into account the diets and habits of an organism. Take the monkey, for example. It is being reported that certain species living in cold, harsh environments are altering what foods they eat during different seasons. In the cold seasons, they are eating fats and carbs to generate the extra heat they need. Then when spring rolls around, they cut out the excess foods and eat their normal diet. “This provides strong evidence golden snub-nosed monkeys forage selectively to balance the macronutrient content of their diet, but also change the balance to meet changes in the nutrients needed — in this case for generating body heat,” (Univ Sydney, 2018).

Another interesting thing monkeys have been found to do is huddle together. “Monkeys that had more social partners — the monkeys they groomed with — would form larger huddles at night than those animals with fewer social partners, allowing them to save more energy for growth and reproduction,” (Univ Lincoln, 2018). By gathering around each other during the cold nights, the monkeys are protecting and helping both themselves and each other. Less sociable monkeys are less likely to survive the winter months because they will have fewer companions to huddle with.

While these two cases may not directly relate to our experiment of body size, each study shows there are several factors that can influence an organism’s thermoregulatative activities. Body size could determine how much more fats and carbs one must eat to stay warm. Being social could determine how large your offspring will be, thus determing how likely they will be to survive. All of these factors are interconnected and correspond to each other in ways we do not quite know. However, these experiments and studies can help us to understand and maybe eventually learn from the reasoning behind the choices each organism makes for survival.

References

University of Lincoln. (2018, May 30). Huddling for survival: monkeys with more social partners can winter better. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 11, 2019 from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/05/180530113118.htm

University of Sydney. (2018, June 8). Monkeys eat fats and carbs to keep warm: Golden snub-nosed monkeys adjust nutrient intake in winter. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 11, 2019 from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/06/180608093646.htm

Belovsky, G.E., and Slade, J.B. (1986, August). Time budgets of grassland herbivores: body size similarities. Oecologia, 70(1), 53-62. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00377110